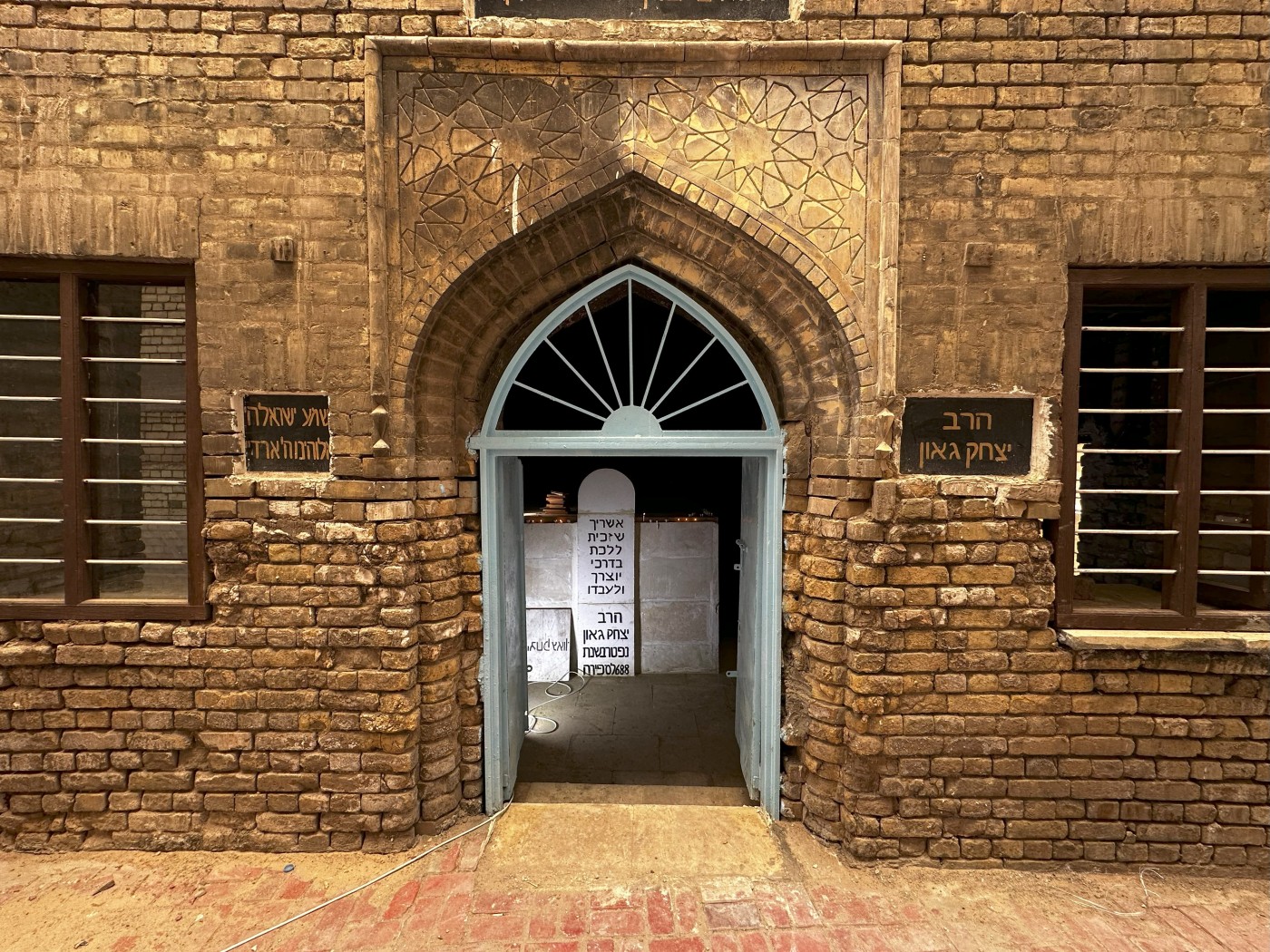

BAGHDAD, Iraq - After decades of neglect and obscurity, the shrine of Rabbi Isaac Gaon has once again come into view for the residents of the Qanbar Ali neighborhood in the Rusafa district of Baghdad. Freed from the layers of dust and rubble that had covered it since the 1980s, the site is beginning to reopen the doors of memory, filled with historical stories about a religious figure who lived in the heart of Baghdad and a cultural heritage long hidden behind crumbling walls.

While it is not unusual to witness governmental initiatives aimed at restoring and reopening heritage sites in Baghdad, the peculiarity of this case lies in the personal and sensitive nature of the location. Recently, National Security Advisor Qasim al-Araji visited one of the most significant Jewish religious shrines, which is attributed to Rabbi (a term in Judaism meaning a wise or skilled man) Isaac Gaon.

The official visit stirred a range of reactions. Some praised the initiative, while others responded with anger and suspicion. The New Region sought to get closer to the real story and visited the site. Reporters spoke to Abu Sajad, a neighbor of the shrine, to understand the developments from the beginning. Pointing to the old building, he said, “About four months ago, we started noticing unusual activity here, workers coming in and out, clearing rubble, and cleaning the place that had been abandoned for many years. For decades, the shrine was buried under heaps of dirt and neglect, sealed by rusty doors, and no one was allowed to enter or even approach it.”

Renonvation being performed at the shrine Photo: The New Region

Abu Sajad continued, “In the past, the shrine was a place of great importance for the people of Qanbar Ali. They used to clean it daily, and many people from different sects would visit it to seek blessings. It had a good reputation, and I personally witnessed many miracles associated with it.”

He added, “After 2003, following the fall of the previous regime, everything changed dramatically. Due to the lack of security, the shrine was looted, and all of its contents were stolen. Everything related to it was lost.”

Abu Sajad recalled how the site became a source of danger afterward, turning into a haven for insects, scorpions, and snakes. This caused foul odors to spread into nearby homes. He said, “We ended up sealing all the entrances to the shrine because the insects and scorpions became a real threat to our peace and health. Many children were bitten and suffered painful stings.”

Regarding the long-standing neglect of the shrine, Abu Sajad explained that government bodies deliberately ignored the site due to religious disputes over its ownership. He said “Every religious group, Muslim or Jewish, claims the tomb belongs to them, and this is what prevents any serious attention to the site.”

He also mentioned that there were once many Hebrew books inside the shrine, but they were torn apart by children and have since disappeared. He recounted the story of an elderly woman who lived in the shrine, taking care of its cleanliness, welcoming visitors, and guarding the place until she died at the age of 80.

Another neighbor, a young man who preferred to remain anonymous, commented as he observed the recent changes to the site, “They fixed the main door, replaced the old tiles, and repainted the façade, which had been cracked and crumbling. They even removed a number of small, abandoned shops next to the shrine, some of which were nothing more than piles of broken bricks.”

He said, “All of this was part of a plan to expand the area around the shrine and better prepare it to receive visitors. The scene has transformed from a neglected ruin into a clean and organized space, conveying a sense of respect and appreciation for the site and its history.”

Jews in Qanbar Ali

The Qanbar Ali neighborhood is one of Baghdad’s historic quarters, located on the eastern side of the capital. This district is known for its traditional atmosphere and cultural heritage, with a long history tied to Baghdad’s religious and cultural diversity. It was once a vibrant commercial and residential area, and the name Qanbar Ali traces back to one of the old Baghdadi families who settled there centuries ago.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Qanbar Ali was among the areas inhabited by many Jewish families in Baghdad. Jews formed an important part of Baghdad’s social and economic fabric, operating shops and practicing their own trades. Like many other Baghdadi neighborhoods, the district was a hub for commercial and cultural activity and included several notable landmarks such as Zaqaq al-Pasha, Abbas Effendi Street, and Sultan Hammoudah. It was also home to one of the oldest Jewish synagogues and was previously known as the Jewish Quarter and the Great Torah Neighborhood.

Alongside their synagogues and schools, Jewish cemeteries were also present in the area, including the shrine of Rabbi Isaac Gaon, who was considered one of the prominent religious figures in the Baghdadi Jewish community. This shrine remained one of the most revered Jewish sites in Baghdad until the late 20th century. However, following the mass emigration of Iraqi Jews in the 1950s and 1960s, interest in Jewish shrines began to decline, and many of these sites became abandoned.

After most members of the Jewish community emigrated from Iraq, and due to the political and social transformations in the country, attention to Jewish shrines in the Qanbar Ali neighborhood gradually faded. Many Jewish landmarks disappeared over time, though the area still retains a strong memory of the period when Jews were an integral part of daily life in Baghdad.

Hebrew writing adorns the Jewish shrine. Photo: The New Region

A look back: Who were the Geonim?

Rabbi Isaac Gaon was a prominent Jewish religious figure who lived in the medieval era. His full name is often cited as Isaac ben Jacob Gaon. He was one of the Geonim, or heads of Jewish religious academies (yeshivot) in Iraq during the Geonic period, which spanned approximately from the 7th to the 11th centuries CE.

Rabbi Isaac lived around the 10th century CE and was the head of the Pumbedita Academy, one of the most important Jewish religious schools in Iraq after the fall of the Abbasid dynasty in Baghdad. The title “Gaon” means “genius” or “distinguished one,” and it was used for senior rabbis and academy heads in that era.

He was among the great commentators and jurists, authoring numerous religious letters and legal responses known as “She’elot u-Teshuvot” (Questions and Answers). Jews from around the world sent him religious and legal inquiries, and he would respond with rulings. He played a significant role in organizing Jewish religious education and establishing the foundations of Jewish legal scholarship outside Palestine.

Some sources suggest that he contributed to shaping the texts of prayers and rituals that remain in use in Jewish liturgy today. He was held in high esteem not only in Iraq but also across various Jewish communities as far as Andalusia and North Africa.

Although multiple Jewish figures bore the name Isaac Gaon, the most famous and influential was the one who headed the Pumbedita Academy in Iraq.

These Geonim were religious and legal leaders, not only for the Jews of Iraq but for most Jewish communities in the Islamic world and Europe at the time. Their centers were two main religious schools: the Sura Academy near present-day Hillah, south of Baghdad, and the Pumbedita Academy near present-day Fallujah. These two schools functioned as religious “universities” and produced some of the most prominent scholars in Jewish history.

The importance of their presence in Iraq

At that time, Iraq was the most important center of the Jewish world after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Baghdad became a highly influential city, and with it, the religious center of gravity for the Jewish people shifted from Palestine to Iraq.

The Geonic period represented the “first golden age” for Jews in Iraq, during which the Jewish community enjoyed a degree of stability and intellectual and cultural prosperity. However, their influence began to decline in the 11th century with the rise of new religious centers in Al-Andalus and Morocco due to the weakening of the Abbasid Caliphate and the deteriorating political situation in Iraq.

Despite this, their scholarly legacy endured, and their religious work influenced Jewish prayers and laws for many centuries. The Geonim, including Isaac Gaon, were architects of Jewish religious identity during a pivotal era in history. Iraq was the heart of this spiritual civilization, serving not only Iraqi Jews but Jewish communities around the world. Until the 1940s, there remained a large Jewish population in Iraq, especially in Baghdad and Basra.

After the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent rise of Arab nationalism, near mass-deportation campaigns targeted Iraqi Jews, particularly through Operation “Ezra and Nehemiah” (also known as “Operation Ali Baba”) in 1950–1951.

As the vast majority of Iraqi Jews left, synagogues and Jewish religious shrines were left without visitors and gradually fell into neglect or were vandalized. During the 1950s and 1960s, openly acknowledging any Jewish symbols became dangerous due to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Anti-Zionist sentiment, often conflated with Judaism, led to Jewish shrines being ignored and, at times, deliberately destroyed.

At certain periods of governance, especially after the 1958 revolution and the fall of the monarchy, no laws existed to protect Jewish shrines or non-Islamic religious heritage. Some shrines were either confiscated and repurposed or neglected due to their loss of official value.

Iraqi cultural and religious institutions in recent decades have rarely focused on preserving non-Islamic religious sites, such as Christian, Jewish, or Mandaean landmarks. As a result, the shrine of Isaac Gaon, like other Jewish sites, was left to either natural decay or human vandalism.

With the expansion of cities and changes in their structure, many historic landmarks, including cemeteries and shrines, were destroyed or removed. Baghdad expanded significantly in the second half of the 20th century, altering the landscape of many historic neighborhoods, including the area around the shrine of Isaac Gaon, which is now seeing a revival.

An information board detailing the renovation work carried out. Photo: The New Region

Reviving religious heritage

Speaking about the shrine, Iraqi archaeology researcher Sabah al-Saadi said the site had suffered from prolonged neglect despite its spiritual and historical importance. Saadi emphasized, “We must not look at the restoration of this shrine as a politically motivated issue. This shrine is not new, it is part of a long history of Jews in Iraq.”

Saadi added, “Iraq has always embraced various religions and sects, and it is only natural that we respect and value the religious sites of all communities.” He stressed that the matter is not about Zionism, but rather about Jews who were part of Iraq’s history.

He expressed hope that the shrine could become a tourist attraction that would raise the area's profile, saying, “This step can help develop the area through infrastructure improvements, boost tourism, and enhance urban and security services. This would benefit Iraq and improve its international image.”

He affirmed that “such initiatives must be free from extremism and hatred. Iraq needs to build bright future prospects,” and continued, “We are in a country rich in history and civilization, and this step opens the door to greater international respect for Iraq and increases people’s desire to visit our country.”

For his part, Iraqi historian and researcher Mohammed al-Atraqchi said this step had long been necessary. He stated, “Iraqi society consists of many religions and sects, and there are many intellectuals and open-minded people who view Judaism as a relationship between a person and their God, just like any other religion. Extremists and fanatics are the ones who see it differently. Therefore, the reopening of the shrine should not cause any sensitivity. On the contrary, it promotes a culture of interfaith coexistence.”

Atraqchi added, “The reopening of the shrine could be a step toward the return of Jews to Iraq, as it was their original homeland since ancient times, just as Jews have long existed in neighboring countries such as Iran, Morocco, Egypt, and North Africa.”

Opposition to shrine restoration

Not all opinions align with the restoration initiative, as some view it as a violation of religious principles that protect Islamic identity. In this context, Sheikh Hamid al-Shiblawi, a cleric, expressed his opposition to such efforts, saying, “The presence of religious and political figures at the shrine of Rabbi Isaac Gaon in the Qanbar Ali area is not permissible.” He noted that such acts amount to the promotion of falsehood.

Shiblawi added “It is unacceptable to establish temples and shrines for non-Muslims in Iraq. This contradicts the principles of Islam, which is the final religion through which God completed the divine message.”

Shiblawi pointed out that visiting non-Islamic sites does not align with the beliefs of a Muslim, explaining that any tendency to acknowledge or promote religious rituals not associated with Islam goes against core doctrine. He stated, “Islam is the religion through which God completed His message, and it is not permissible to promote other religions that God has nullified in the Holy Qur’an.”

He affirmed that Iraq should remain a host for Islam alone, without external religious influences, and called for adherence to religious constants.

Political questions and local sensitivities

In an exclusive statement to The New Region, Iraqi security expert Majid al-Qaisi said the visit by National Security Advisor Qasim al-Araji to the shrine of Rabbi Isaac Gaon carries significant security and political dimensions, far beyond a cultural or religious event.

He explained, “This step marks the beginning of several potential gains, including enhancing local security through the promotion of religious tolerance and peaceful coexistence, preserving Iraq’s cultural and historical heritage, improving the country’s international image, and encouraging interfaith dialogue.” He also pointed to “the importance of supporting local labor by involving Iraqis in the rehabilitation process and reviving the historical memory of the Jewish community that was once an integral part of Baghdad’s social fabric.”

However, Qaisi cautioned that political and social sensitivities may lead to mixed reactions, especially given the tense regional environment. He noted that inciting posts have already begun to surface on social media platforms such as Facebook and X.

He said, “Some armed factions or extremist groups may exploit the event to provoke sectarian tensions,” reminding that Iraq remains fragile in terms of security and has not yet fully emerged from the sectarian division phase.

Qaisi emphasized, “Every reform project initially faces challenges, but with wise management and sufficient time, these challenges can be turned into opportunities to strengthen social stability, which in turn will reflect positively on the overall security situation.”

From a security standpoint, Qaisi recommended imposing strict measures to protect the shrine and its surroundings, noting potential threats from terrorist or extremist cells in the area. He called for reinforcing the capabilities of local security forces.

He also pointed out, “The funding sources of the project may pose another challenge, especially if they are linked to international organizations or Western Jewish entities, which could raise suspicions and intensify political and sectarian controversy.”

Qaisi concluded by saying, “The timing of this initiative has raised questions and local criticism due to political and religious sensitivities. There is no conclusive evidence directly linking the project to current regional events, such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or tensions with Iran, but the sensitive regional context makes such projects vulnerable to political interpretations. Local criticism suggests that other cultural and religious priorities may be more urgent in the eyes of some. The possibility that funding arrangements with international or rabbinical organizations were finalized at this time only adds to these questions.”

The shrine's entrance. Photo: The New Region

The return of Jews: Reconciliation or interest?

Dr. Ali Bakht, head of the Ufuq organization and a researcher specializing in minority affairs, told The New Region “The Jews, as a social and religious component in Iraq, have been subjected throughout history to social and legal marginalization, which reflects the impact of restrictive policies implemented during certain periods.”

Bakht noted that “Iraqi Jews, despite being widely displaced during the past century, still hold Iraqi nationality and are considered part of the social fabric.”

He explained, “Iraqi law does not prohibit the return of these citizens, but a legal obstacle exists in the form of the citizenship revocation measures imposed on those who emigrated to Israel in 1950. These require legal remedies for any return efforts.”

Bakht considers the restoration of the shrine of Rabbi Isaac Gaon an important step in embodying Iraq’s pluralistic identity. He affirmed that “Iraq has been and remains a model for coexistence among different sects and religions, and these initiatives should be viewed within the framework of promoting social diversity, away from entanglement in political issues tied to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.”

Regarding the potential return of Jews to Iraq, Bakht pointed out that despite regional and international tensions, the conditions for the return of the Jewish community at the present time are difficult and dependent on the availability of a stable political and security environment. He also cited the impact of economic dynamics, which could help attract Jewish families back to the country, referencing examples from other nations such as Iran and Morocco that have benefited from minority communities to enhance their local economies and boost diplomatic representation on the global stage.

Ali Abbas, a civil society activist, believes the official visit to the shrine of Rabbi Isaac Gaon represents a public gesture to encourage Jews of Iraqi descent to visit Baghdad. However, Abbas expressed concern that politicians and government officials may exploit such steps for political gain, potentially turning the issue into a tool for narrow political interests.

Abbas stated, “I fear that Iraqi Jews will be exploited as a kind of ‘commodity’ to serve specific agendas within the current or future governments. Nevertheless, as activists, we generally support any effort that helps strengthen the connection between Iraqi Jews and their homeland, in the hope that it contributes to rebuilding bridges between Iraq and its citizens of all sects without turning such matters into instruments for political gain.”

Facebook

Facebook

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

Telegram

Telegram

X

X